There is a feeling of competition and closure in catching a spring trout on fly tied with the fur and feathers of our autumn quarry. There is joy in having a few beers over a hot grill with dove poppers. As ethical wildlife stewards, making full use of the animals we harvest is a celebration. Bringing game from field to table is an art. The meats we harvest are often lean and challenging to cook. Some dining at our tables, in fairness, have not acquired the yearning to taste wild meats. For every table guest with a romantic enthusiasm to join in sharing the take, there will always be someone with a mental objection to eating an animal that you have harvested.

Preparing meals from big game, fowl, and caught fish is routine in our family. It’s damn good eatin’ and if nothing else, it keeps us healthy! A meal of game is anticipated by guests at our table, both to celebrate the divinely ordained fellowship of sitting down for a meal and to honor good times in the field.

By default, let it be said that I love to grill. I love cooking on wood and charcoal. I enjoy standing outside watching smoke curl and embers glow. I’m guilty of sneaking a couple more cold beers out than I should. I love positioning out from the confusion of the house to tell stories with the guys. I love teaching my boys how to grill. I have and always will put wild game on the grill. This can be as simple as searing little cutlets hidden in bacon, cheese, and peppers for dunking in sauces. Roasting whole cuts of game over fire and smoke can also feature the meat in its most flavor foreword presentation, but this requires mastery to do well.

This is not a piece about grilling game . . .

The culture of our hunt club is too stay in the bar and living room until a bell rings announcing that food has been placed on the dining room table. When supper concludes the same bell is rung, we retire to the living room without seeing much of the staff that cooked for us. As a young man, my fascination pushed me into the kitchen. Eliza is an eighty year-old woman that has cooked for the house, by best account, her whole life. I imagine in our conversation that she was taught the craft by her mother and grandmother, and I see the same food-way legacy continue as her granddaughter is often in the kitchen with her. Most of her offerings are fried, some of the best blue plate soul food you have ever imagined. The alchemy that pulled me into her kitchen are stews. To be able to witness the care and tradition in her process moved me to learn.

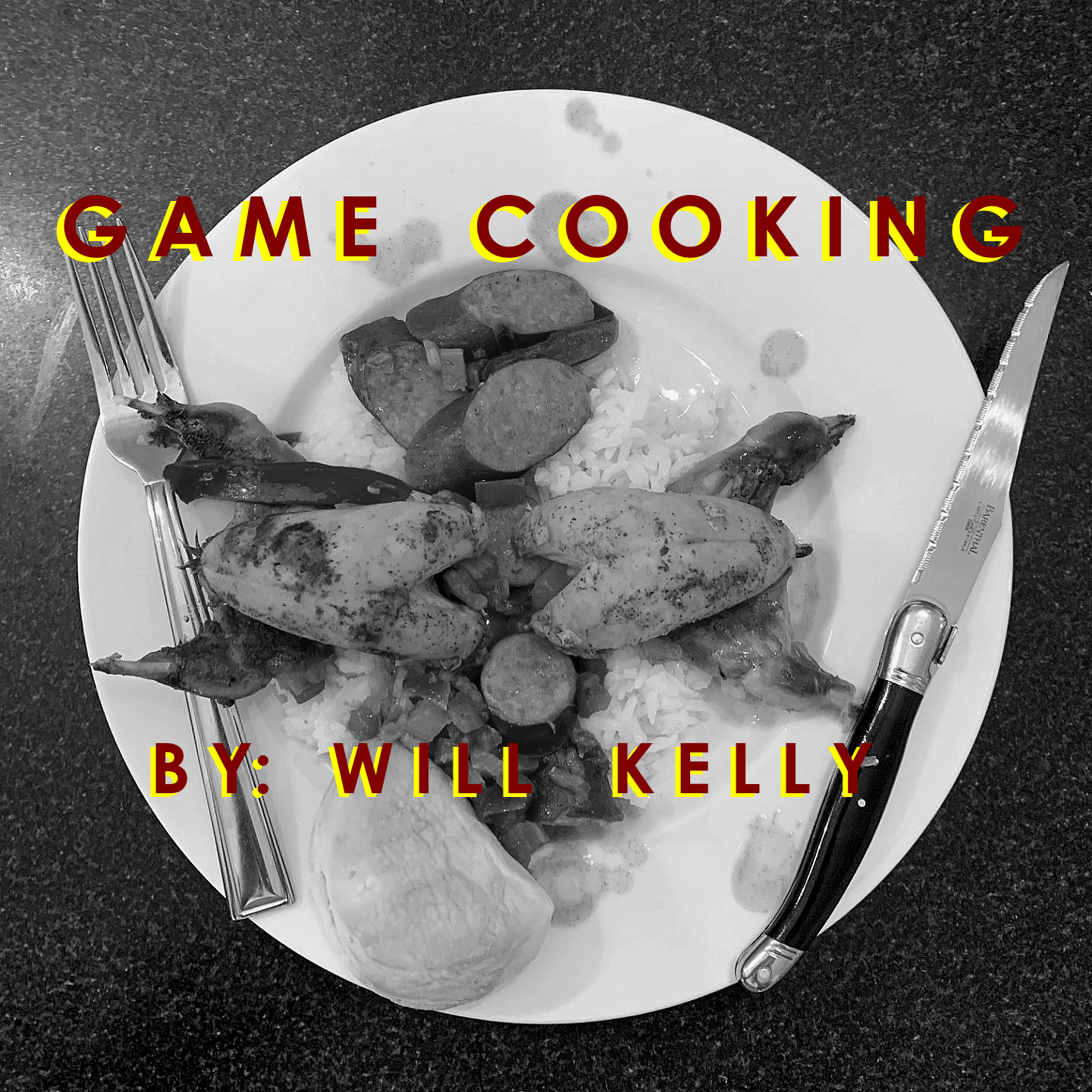

My goal when I sat down to write was to compose a short piece about cooking game with a recipe for quail gumbo. Here in the fourth paragraph, I believe it’s necessary to compel your interest as a reader toward a cooking method, rather than a step by step to a recipe. After nearly twenty five years of standing over a grill, my new passion is minding an enameled cast iron pot in the kitchen. Single pot cooking is perfect for game, especially to provide a hearty meal in the cold months of hunting season. With a few adjustments of ingredients, the technique can produce traditional Southern favorites from Chilis to Brunswick stew to Gumbos, even lending itself to Osso Buco style dishes.

Here’s how it generally goes down in my kitchen:

I plan on cooking for around an hour, but plan on these meals to simmer anywhere from 2-5 hours before being served. I have to admit, while they don’t present as eloquently on the plate, most of these often taste even better reheated as left overs a few days later.

The Armaments: A big cutting board, a great and sharp chef’s knife, a large enameled cast iron pot (Dutch oven or Le Creuset), a big wooden spatula, some great music, and nice drink on the counter.

The Ingredients: 3-4 pounds of game meat, a fat meat to flavor and “grease the pot”, good oil, fresh trinity or mirepoix vegetables (onion, celery, plus bell peppers and/or carrots), good fresh seasonings (garlic, fresh herbs, salt, pepper, and seasoning specific to the recipe ranging from jerk to curry flavor). For the Cajun Dishes dishes: great andouille sausage. If the spirit moves, especially with duck— finish the stew off with fresh shrimp, oysters or picked crab meat. THE BOTTOM LINE: Often you don’t pick the recipe, but rather the availability of ingredients, from the protein to the seasonings to the vegetables, fresh and frozen alike, dictate the final dish. All along the way a cooking method, tried and true from the hotels of France to the back kitchens of the lowcountry, is employed to ensure a tasty outcome. Your job as a cook is simply to control the chemistry of proteins, acids, fats, and salts.

The Method:

– First cook the game meat, presumably on the bone. I generally start with a good browning in a thin layer of oil, then cover for some time at a lower heat until I have a good certainty that when the meat begins to cool that it is cooked enough that I can set it aside and pick the meat off the bones later. (I’ll throw in right here- if you don’t have a pheasant in the freezer, you can grab a rotisserie chicken and move along.)

– When the meat is reserved to the side, I throw a few chucks of fat meat in the pot. This can vary from pork lardons, fatback, sidemeat, or diced bacon. I keep it moving at medium heat. Off to the side I’m cutting up the base aromatic vegetables, this is usually the Cajun Trinity for Gumbos and Lowcountry Stews or a French mirepoix for the less spicy dishes. As the pork meat begins to produce a nice oil and brown the pot’s edges I work in the veggies, keeping them moving. The goal is to sauté them with plenty of heat and create a sugary caramelization rather than to let them sweat and let the pot get “wet”. If I’m adding sausage to the dish, it goes in now. You’ve got to keep it moving.

– As the onions turn opaque and lean over to a light brown, I usually pick an appropriate acid to deglaze the pot. Depending on the desired flavor profile this is usually a white or red wine that been hanging back unfinished in the ‘fridge. With the heat still high, it is poured in the pan and swabbed around the edges reclaiming all of the brown bits. As this liquid nearly reduces to nothing, it is time to add the base cooking liquid. This can be a store bought stock (chicken, vegetable, seafood, beef) appropriate to the dish.

– As the stock comes to a boil, I pick the meat from the game and add it to the pot. I also add any vegetables appropriate to the dish (for example okra for gumbo, corn and peas for Brunswick stew). I turn the pot down to a low simmer once I see a boil, I stop sneaking little sips of my drink and lean on the counter and enjoy a long one.

– I think for a bit about seasoning the pot. This is the time to execute seasoning as all the ingredients are cooked— they just haven’t married one another yet. I’m not embarrassed to admit that I use Zatarans, Cavenders, Old Bay, and Tonys, I like Mrs. Dash and store bought Herbs Provence— but given the chance, nothing is better than garden grown herbs and spices and I use them whenever available.

– The simmer period is as long as you wish, but I like at least three hours. Sometimes, esp. if you have a less than reliable cooktop, I move the pot to the oven at 225 degrees.

– Almost every dish I make is served over a portion of rice with a contrasting vegetable (raw against stewed, acidic against hearty, etc.)

Skol, Bon App, Sliante, and Cheers,

Will Kelly is a RCS contributor and a good friend.

Annnnnd, now we’re hungry! Great read. Game cooking & eating has became a recent interest of mine and this piece just built up more hype.